The Rise of Sinophobia on Twitter during the Covid-19 Pandemic — Conceptual Part 1

Written by Philipp Wicke and Marta Ziosi for AI For People — 23.05.2020

In this article, we will have a look at the conceptual underpinnings of the first episode of our series on “Analyzing online discourse for everyone”. In this first part, we will concern ourselves with the socio-historical background which set the stage for the rise of Sinophobia during the Covid-19 pandemic. This article better prepares the reader for our more specific analysis, which follows in our next episode.

Why China and the Virus?

During the Covid-19 pandemic, “Chinese Virus” or “Wuhan Virus” emerged as controversial terms for the virus. While the expressions may appear neutral to some, simply relating to the physical origin of the virus, to others the terms are instead linking ethnicity to it. Regardless of how we settle the debate, we argue that language plays an important role in this context. As Boroditsky suggests, the way we talk shapes the way we think. Equally, the way we talk about a virus shapes the way we understand it and relate to it as a concept. That is why we decided to take a deeper look at how people talk on social media about the virus, in relation to China. Given a worrying rise in Sinophobia during the outbreak, we decided to answer the following question through our research, ‘‘To what extent does Sinophobia feature in Covid-19 tweets?’. Before presenting our more specific findings in our next episode, we hereby place Sinophobia in a broader socio-political context.

What is Sinophobic and what is not?

In the 1980s, HIV became associated with Haitian Americans, in 2003 SARS was associated with Chinese Americans and in 2009, H1N1, or swine flu, was associated with Mexican Americans. Either because spreading among a certain community or because originating from a certain territory, infectious diseases are often inadequately associated with a population or a country.

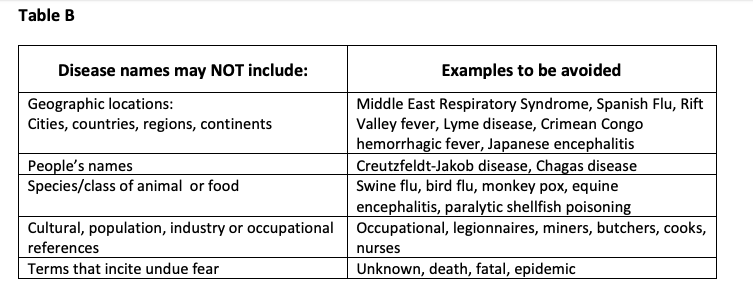

Published in 2015, WHO guidelines for the “Naming of New Human Infectious Diseases” discourage the use of ‘geographical location’ and ‘cultural or population references’ in naming diseases.

Among those, they cite ‘Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, Spanish Flu, Rift Valley fever, Lyme disease, Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever and Japanese encephalitis’ as examples of names to be avoided. Pairing an illness with a country or an ethnicity leads to a personification of the virus. On one hand, this is tempting as it allows us to more clearly identify what would otherwise be an abstract threat. On the other, it runs the risk of equating an illness — a disorder which affects a population — with the population itself. This might wrongly suggest that a population ‘carries’ the disease by means of its ethnicity or even that it played a role in generating the illness. The latter does not come as news, given the conspiracy theory about Covid-19 being created in a lab in Wuhan by Chinese researchers.

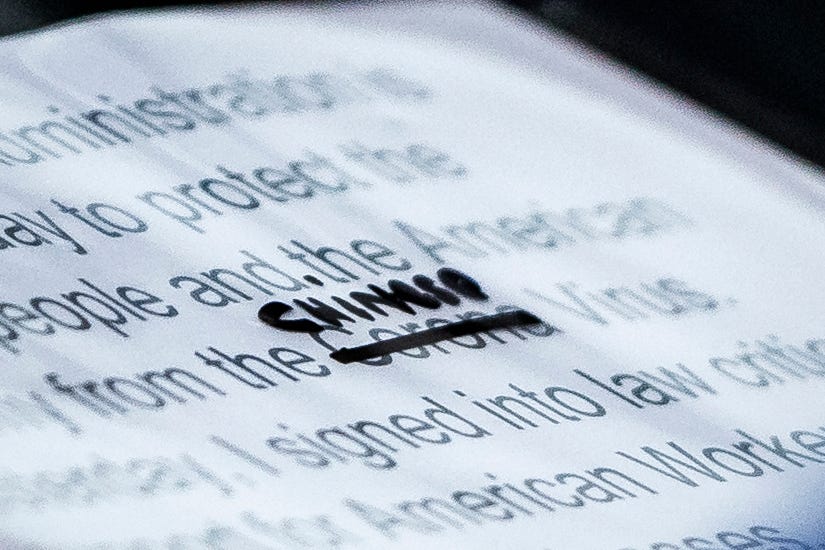

Notwithstanding the above considerations, the terms “Chinese Virus” and “Wuhan Virus” appeared in several media reports, especially in the early days of the outbreak. As a matter of fact, many people — among which highly ranked politicians — do not consider the term to be discriminatory. For example, the President of the United States, justified his calling Covid-19 the “Chinese Virus” as:

“It’s not racist at all. No, it’s not at all. It’s from China. That’s why. It comes from China. I want to be accurate.” (March 18)

Indeed, it could be argued that the name simply suggests the location where the virus originated. However, as a matter of fact, racist acts and harassment against Asians which were already on the rise, registered a peak in the third week of March, when over 650 racist acts where reported by Asian Americans just in the US.

The above suggests that, even if not intrinsically racist, terms such as ‘Chinese Virus’ or ‘Wuhan Virus’ are consequentially so, as they negatively impact the lives of many Asians all over the world.

A bit of history

It is important to consider that racist acts against Asians are not solely traceable back to Covid-19. History reveals that in the case of Asian Americans — which are also the ones mostly targeted by the present discourse— there exist several precedents. Let us start from far back in time, with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 in the US. Building on the 1875 Page Act, which banned Chinese women from immigrating to the United States, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States. At the time, Chinese composed only .002 % of the US population. Nevertheless, many Americans — especially on the West Coast — attributed declining wages and economic ills to Chinese workers. This condition was only relaxed in 1943, when 105 Chinese were allowed to enter per year.

Nearby, in Canada, the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration was appointed in 1885 to obtain proof that restricting Chinese immigration was in the best interest of the country. The Commission wrote a report which described Chinese as immoral, dishonest, unclean, prone to disease and incapable of assimilation. These judgments were largely based on common stereotypes rather than any research.

Anti-Chinese sentiment rose again in the US during the Cold War, due to McCarthyism. During that era, suspected Communists were imprisoned by the hundreds, and some ten or twelve thousand of them lost their jobs.

From 1965 until today, the modern immigration wave from Asia to the US has accounted for one-quarter of all immigrants who have arrived in the country. In the US, the population of Asian Americans counts approximately 22,408,464 people, with Chinese being the largest group.

How does history relate to the present?

The past history of racism and the significant presence of people from Asian origin — especially Chinese- in the US population does not simply serve as a precedent, but also as an admonition for the present. If not carefully addressed, Sinophobic trends rising during the pandemic could have serious, impactful consequences. These considerations lead us to search for those Sinophobic trends, which find their origins in history, in the present context of Covid-19. We decided to focus our research on Twitter, one of the main ‘places’ where modern discourse takes place nowadays.

The points raised above lead us to consider as Sinophobic hashtags such as ‘#ChineseVirus’, ‘#Chinavirus’ and ‘#Wuhanvirus’. Nevertheless, our research revealed that these are not the only Sinophobic terms currently in use.

Digging deeper

In further conducting our research, we discovered that the above terms were not the only terms in use which were affecting Asian communities. A study by Schild et al. (2020) found that real-world events related to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic coincided with an increase in the use of Sinophobic slurs such as “chink,” “bugland,” “chankoro,” “chinazi,” “gook,” “insectoid,” “bugmen,” and “chingchong” in online discourse on Twitter and 4Chan.

Admittedly, given the increasing dominance of China in the newly emerging World-order, its name is often evoked in multiple current contexts. Examples of these are the trade-war between the US and China, the South-China Sea dispute, the Uyghur ethnic minority and the ongoing tensions with Hong Kong.

These disputes have given birth to their own discourses, often accompanied by negative terms towards the Chinese Government.

We thus considered that some of the above Sinophobic slurs might not be strictly related to the virus. For example, given the pressure of China over Hong Kong, terms such as ‘chinazi’ are often used in the context of the HK protests to express negative sentiments towards the Mainland.

The same study by Schild et al. (2020), however, discovered also new emerging slurs and terms more directly related to Sinophobic behavior, as well as the Covid-19 pandemic. Examples of these terms were “kungflu” and “asshoe”. While the first one associates the virus (wrongly stated as ‘flu’) with traditional Chinese Martial Arts, the second aims to make fun of the accent of Chinese people speaking English.

Where to next?

The socio-historical excursus which this article represents displays the complexity of the case at hand. People’s perception of what is Sinophobic changes, though the consequences stay. Furthermore, Sinophobic terms often generate from multiple contexts and while sometimes they are directed towards the people, sometimes they are aimed at the actions of the Chinese government. In our next article, we will present you with our own findings in the search for Sinophobic words in the context of Covid-19. We will consider as Sinophobic words that are blatantly so, like “chink” or “bugland”, as well as more debated terms such as ‘’Chinesevirus” or “Chinavirus”. We hope that this first article set the stage for you to better grasp what follows.

The Rise of Sinophobia on Twitter during the Covid-19 Pandemic — Conceptual Part 1 was originally published in AI for People on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.